Talking about Your Child’s Diagnostic Discovery

You investigated (or perhaps are investigating) an autism diagnosis for your child. Your child’s medical professional confirms this. What next?

Likely, you’ll need time to feel your feelings. This is a journey! Take care of yourself as best you can while you process. Connect with other families. Read what autistic adults have to say about their experiences as children (and as adults). Take everything anyone tells you with a grain of salt, as your child will develop in their own way, and in their own time. No one can predict this trajectory in absolute terms.

Here are some things to keep in mind as you navigate what this means for your child:

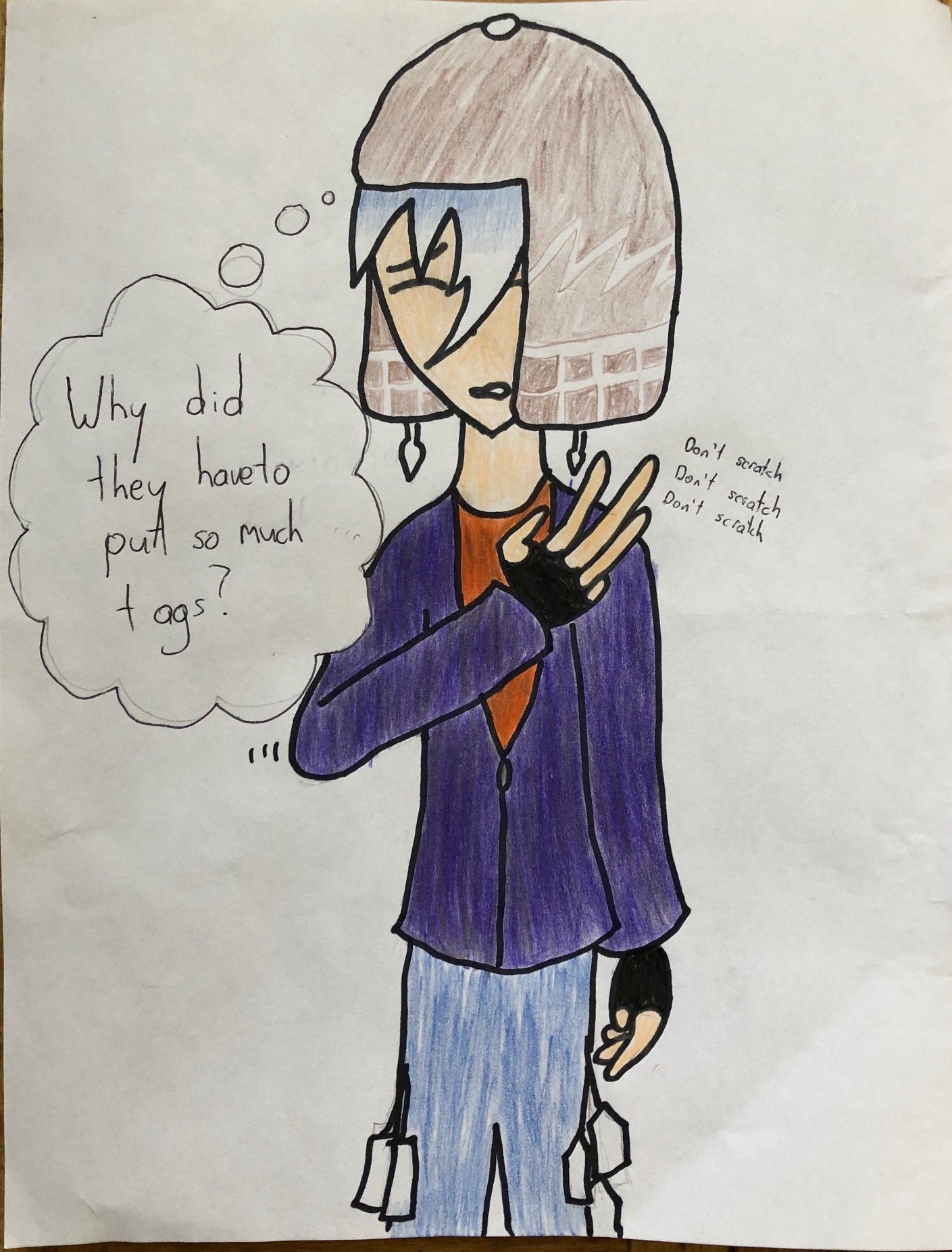

Drawings of one of my students (shared with permission).

Your child experiences the world differently than others, and possibly, differently than you. This may mean their senses are amped up or down. They may notice sensory stimuli, like fluorescent lights flickering 60 times per second, or hear the electricity buzz of plugged in appliances that others miss. Certain foods may be unbearable. Unexpected touch may be shocking. Eye contact may be painful. On the flip side, they may not feel or have the words to describe when they have a tummy ache, or notice the cold or heat. They may love a variety of strong flavours or smells. They may be excited by flashing colours and lights.

Your child experiences emotions, especially perceived rejection or failure, viscerally. A study showed autistic children are more likely to internalize shame (I’m a bad person) than guilt (I did one bad thing). They experience corrections and criticisms frequently throughout the day, often related to things they don’t understand or do differently - not worse, just differently! - than others. They will feel rejection during many interactions, sometimes multiple times a day, when they make a perceived misstep (which is really caused by a difference in communication styles). They are often given more goals and things to work on than everyone else, and can feel this acutely. What is wrong with me, that I need so much fixing? Of course, they do not need fixing - they need understanding, nurturing of their strengths and interests, and support with what is harder for them.

Miscommunications happen, and are often perceived as the fault of the autistic person — when in fact, communication is a two-way street. When an interaction does not go as one would like, this can be a signal of a mismatch in communication style, rather than something the autistic person is doing wrong. This is called the ‘Double Empathy Problem’, a concept by Damian Milton (2012). A recent study by Crompton and colleagues (2020) actually tested this out. They created three groups and tested their ability to relay a story in a broken-telephone style chain, and also had participants rate their sense of rapport with the group. Here’s what happened:

Results:

Group 1 - fully autistic - effectively relayed more details about the story and had higher rapport ratings

Group 2 - fully non-autistic - similar outcomes as the fully autistic group!

Group 3 - a mix of autistic and non-autistic - fewer details remembered and lower ratings of rapport between group members

This is a good reminder that autistic folks generally communicate well and find belonging with other autistic people, and that non-autistic folks may need to adjust how they communicate when talking with autistic folks! So, if your child has friends who are also autistic or otherwise neurodivergent, encourage these. Often we are best understood by people who are like us.

How you talk about autism has a life-long impact. They are, and have always been, autistic. They have not changed overnight. It’s important that your child not feel any grief, anger, or discomfort you may have when you or a medical professional shares that they are autistic. Practice saying it in a mirror until it flows as easily as saying your child is left-handed or has curly hair. How we frame this core part of their brain wiring - the framework from which they view and experience the world - will impact how they see themselves.

Remember, they will absorb messages about autism whether you share their diagnosis or not - they may hear it bandied about as a negative insult in the school yard, or they may see an amazing presentation that frames autism as a way of being. Whatever the source, these may already have influenced any rudimentary understanding of autism and autistic people your child may have, and ongoing negative messaging will make this harder later. Your framing can give them the language, ways of thinking about autism, and coping tools to counter the negatives (internally and/or externally to others, if comfortable doing so) and understand misinformation, stigma, autistic experiences, and their own needs in healthy and compassionate ways.

Regardless of when you share, your child will likely be coping with pervasive feelings of difference, exhaustion from trying to mask/camouflage to not stand out from peers, and the extra effort of navigating a world with many sensory, social, and academic demands. Autistic adults or teens reflecting on later knowledge of their diagnosis most often report relief at having explanations for this feeling of difference. The label can legitimize their experiences and help them figure out where and how to safely be themselves, which people accept and love them as they are, and how to manage the extra demands and stressors they experience. This can reduce self-pressure, stress, and improve their quality of life. Those who find out later especially struggle with low self-esteem and shame as a result of comparing themselves to peers without the understanding and explanation to frame their experiences. Fortunately, research also shows that more support and time can help them to embrace this identity and find the positives (e.g., access to accommodations, relating to other autistic people, gradual self-acceptance). But imagine if there weren’t as much harm to undo?

Labels also help them to connect to a community. They are not alone, or the only person who has these experiences. Research shows positive community identification protects mental health in the longterm, for autistic people throughout their lives. The Zebra Analogy shared on Twitter helps to highlight this: ‘“Why do you need a label?” Because there is comfort in knowing you are a normal zebra, not a strange horse. Because you can’t find community with other zebras if you don’t know you belong. And because it is impossible for a zebra to be happy or healthy spending its life feeling like a failed horse.’

Explanations of autistic traits, strengths, and areas of difficulty can help them to develop their self-understanding and self-advocacy skills. They can use this language to advocate for themselves with teachers when they need help and to explain why; and they can select when and who they might share with in other contexts. Sometimes they may be more comfortable finding other ways, such as describing traits without the label - “sometimes I have trouble hearing and focusing on what you’re saying when there’s a lot going on all at once”.

Transparent conversations about different experiences of members in the household can also give you tremendous insights into your child’s experiences. You can normalize that there is no “normal”, celebrate uniqueness, and also discover what barriers they might be experiencing that they haven’t shared with you. Having a safe place/people to talk about instances that frustrate, confuse, or worry them opens up the opportunity to collaboratively problem-solve, build skills and understanding together, and prepare them for future situations with greater agency and clarity.

Talking about Autism with Your Child

Do your research. Autism is lifelong. It is not a disease or illness. Dispel the myths and affirm your child’s experience.

Look up and listen to autistic adults. They were once autistic children! You can often find them by searching the hashtag #ActuallyAutistic on TikTok, Twitter, and social media.

Manage your feelings and reactions, as described above. I’ve worked with families for over a decade and almost always hear that it was much more emotional for the parent, and that in many cases, the child did not seem particularly shocked or upset. (Obviously how you convey this information matters.) Children around age 8 or older already may feel different than peers, but may not have any explanation for why they feel like outsiders or unsuccessful in comparison besides self-blame. Giving them some answers helps them make sense of their experiences and understand that they have done nothing wrong.

Many autistic people prefer identity-first language (autistic) to person-first (with autism) because it acknowledges how much their neurology impacts their relationship to the world and people in it. It’s a descriptor, like creative, gifted, artistic, etc. Remember, the word ‘autistic’ is not shameful — just as being autistic is not shameful — and should never be said in a tone that conveys it as such.

Attribute both strengths and challenging aspects to autism. It can be easy to talk about autism only when referring to the parts that are hard. Autism comes with challenges, of course, but it also brings your child a unique perspective, that sense of humour, their enthusiastic curiosity and love of learning, their incredible memory for facts about their favourite topics, and so much more. It breaks my heart when kids hate their autism because it has only been presented as associated with social exclusion, difficulty with getting school work done, “bad behaviours”, etc. Many of these difficulties can be addressed by making changes to the environment and how everyone else behaves! Tell your child clearly that autism gives them their special talents and gifts (for example: understanding computers way more than anyone else, or being able to read at a much higher level), but also makes some things harder for them - like making friends, coping when things don't go as they would like, or being more sensitive to loud noises and busy environments. Make sure your examples are specific to your child!

Let them know you are going to help them figure out things that make them more comfortable and confident in their developing areas. They are not alone and all humans work on — or work around — things sometimes.

Share examples of autistic individuals who are thriving - with different examples of success. Try to find representations that show fulfilling lives and hobbies, rather than videos that talk about autism as a grand tragedy or without hope for the future.

Some Resources to Look at & Discuss with Your Child

Always review resources and find ones that will be more likely to resonate with your child. Autism is so varied that you want to be sure your child can relate to any books, videos, or materials you introduce them to initially. Later on, you can move on to more in-depth conversations, by showing a variety of topics related to autistic experiences and discussing what your child feels applies to them and what doesn’t. Here are a few places to start:

BOOKS & READINGS

Some books by autistic authors.

Find books by autistic authors or neurodiversity-affirming authors at an age-appropriate level. I’ll link to Amazon so you can preview but you can often find for free as readalouds on YouTube, use libraries, or buy in local bookstores.

My Autism Book: A Child's Guide to their Autism Spectrum Diagnosis by Tamar Levi & Glòria Durà-Vilà

All My Stripes: A Story for Children with Autism by Shaina Rudolph and Danielle Royer

I’ve Always Had A Voice by Tania Wieclaw

Just Right for You by Melanie Heyworth

The Secret Life of Rose: Inside an Autistic Head by Rose and Jodie Smitten (autistic daughter and mom authors!)

All Brains Are Wonderful by Scott Evans (general neurodiversity)

Uniquely Wired: A Story about Autism & Its Gifts by Julia Cook

The Autistic Boy in the Unruly Body: A NeuroInclusive Story About Apraxia by Gregory Tino (free companion guide here).

My Brain is Autistic: A NeuroInclusive Story from NeuroClastic

NeuroWild (an autistic speech language pathologist) created a brilliant visual story of what it means to be autistic found here: Facebook Post

It's Just a ... What?: Little Sensory Problems with Big Reactions! by Hartley Steiner —> good for discussing sensory differences

Weslandia by Paul Fleischman —> though not about autism, it’s about an innovative thinker whose curiosity and dedication to his passion - and his lack of conformity - makes him stand out in positive ways.

A Kind of Spark by Elle McNicoll

Afrotistic by Kala Allen Omeiza

The Spectrum Girls’ Survival Guide by Siena Castellon

Being Autistic (And What That Actually Means)

by Niamh Garvey and Rebecca Burgess

Can You See Me? by Libby Scott & Rebecca Westcott

Different, Not Less: A Neurodivergent’s Guide to Embracing Your True Self and Finding Your Happily Ever After by Chloe Hayden

Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty

How To Be You: Say Goodbye to Should, Would and Could So That You Can by Ellie Middleton

VIDEOS

Search for videos highlighting cool jobs and things autistic people can do (initially). Later, when your child is better able to identify their own difficulties, watch videos highlighting some of the challenges experienced by autistic people and what some of their tips and coping mechanisms are. You can also ask your child what things help them in the situations they find hard. YouTube and TikTok are great resources! Here are some videos you may wish to check out.

NOTE: Please preview first to see if your child will be interested and what you feel is most appropriate for your child. The videos linked below represent different ages and may contain sensitive content or triggers. Sometimes, language and terms may be outdated or inaccurate. While I aim to find examples that are current and are also representative of the full range of autistic diversity, there is a ways to go! Please let me know if there are videos you’d like to see added to the list!

This video is great for autism in girls and was made by autistic sisters!

BBC - My Autism & Me - a documentary featuring several different autistic youths.

Autistic Professions & Passions - a playlist of autistic people doing cool things! - Preview first! (Updating on an ongoing basis)

Autism Self-Advocacy - a playlist of autistic people talking about things that are for them and how they cope - Preview first! (Updating on an ongoing basis)

CHILDREN’S TELEVISION

Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood - read how my student actually voiced the autistic character!

Arthur - had an episode with an autistic character.

Thomas the Tank Engine - will soon have an autistic train voiced by an autistic actor!

Supports that Benefit Autistic Children

Drawings of one of my students (shared with permission).

It can be hard to navigate a world that feels overwhelmingly chaotic and unpredictable. Harder still is what feels like constant criticism, punishments, and raised voices. Many autistic adults talk about the legacy of therapies that made them feel broken, ashamed of who they were, and left them unable to self-advocate. As a rule, you will want to seek out neurodivergent-affirming therapies or therapists, and avoid programs and people that aim to “fix” or “cure”; which make children hyper-anxious about getting things right; which teach a standard and inflexible response when we exist in a non-standardized world; or which aim to make an autistic child seem more neurotypical. More than anything, autistic folks need people and places to feel safe and supportive. Here are some things to try:

Love and understanding

Identifying sensory and emotional needs and supports through neurodivergent-friendly occupational therapists

Enhancing communication through neurodivergent-friendly therapists and alternative and augmentative communication devices

Accepting autistic ways of being. Consider whether what you or others are asking of autistic children is reasonable, necessary, fair, and achievable, or whether there is room for something to be done in a different way

Explaining the “why” of rules and expectations

Gentle reminders - and picking your battles - can go a long way!

Talking about your own difficulties and the strategies you use, to normalize the idea that we all are works in progress and everyone needs help or strategies sometimes - with or without autism

Opportunities to play and engage with their passions as they like

Breaks, even if they don’t look like they need it. Just build it in!

To be asked what they need and what helps them in various situations

Access to different sensory tools. Find a variety of tools and teach how to use them - as a family!

Access to a quiet space for downtime, especially after draining events like being at daycare, school, or a social interaction.

Plan break and exit plans, for social situations

Being allowed to stim (channel energy and anxiety) at home. Have a stim dance party!

Opportunities for control of their environment - choice, input, a chance to practice making decisions

Let them decide what they want to learn and work on, when they are ready

Predictable, calm adult reactions and responses and help to cope when things feel unfair or overwhelming

Adults who model self-care and self-regulation skills, including taking breaks when upset and before talking about challenging moments

Collaboratively problem-solving. I am a big fan of the work of Dr. Ross Greene which helps to build communication, problem-solving, self-confidence, and understanding between adults and children.

Nurturing their strengths, passions, and expertise.

Being listened to. Ask them questions about their passion areas. Engage in their interests with them, when possible. As adults, we find friends who like to talk about the same things as us. Why not give them conversational experiences/practice that engage them and are also a closer model to what happens when you find your people?

Clubs and activities related to their interests where they may make friends who have things in common

In Case No One’s Told You . . .

Parenting is the hardest job in the world — one that’s filled with never-ending curveballs! Adjusting to new information like a diagnosis can make it seem even harder.

Let me remind you: no parent is perfect or gets it right all the time. Just like we’re trying to help our children to understand it’s okay to learn and grow and have missteps along the way, it’s okay for you, as well. You’re already a step ahead by seeking out this information!

So, in case no one’s told you, thank you for seeking out ways to talk about autism that validate your child and make them feel less alone.

Thank you for helping them to discover their strengths, sources of joy, and passions.

Thank you for listening.

SOME REFERENCES

Crompton, C., Ropar, D., Evans-Williams, C., Flynn, E., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2019). Autistic peer to peer information transfer is highly effective. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/j4knx

Evans, J. A., Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., & Rouse, S. V. (2024). What you are hiding could be hurting you: Autistic masking in relation to mental health, interpersonal trauma, authenticity, and self-esteem. Autism in Adulthood, 6(2), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2022.0115

Howe, S. J., Hull, L., Sedgewick, F., Hannon, B., & McMorris, C. A. (2023). Understanding camouflaging and identity in autistic children and adolescents using photo-elicitation. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 108, 102232–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2023.102232

Huws, J. C., & Jones, R. S. P. (2008). Diagnosis, disclosure, and having autism: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the perceptions of young people with autism. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 33(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250802010394

Jóhannsdóttir, Á., Egilson, S. Þ., & Haraldsdóttir, F. (2022). Implications of internalised ableism for the health and wellbeing of disabled young people. Sociology of Health & Illness, 44(2), 360–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13425

Milton, D.E.M., Heasman, B., Sheppard, E. (2020). Double Empathy. In: Volkmar, F. (eds) Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6435-8_102273-2

National Autistic Society. (n.d.) Masking

OMGImAutisticAF. (2022, Aug 29). Twitter post.

Richards, L. (n.d.) How to Tell Your Child About Their Autism Diagnosis - Child Mind Institute